On this day 15 January 2009, 12 years ago, Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger achieved an amazing feat of airmanship. All souls saved and against all odds!

On January 15, 2009, US Airways Flight 1549 with call sign ‘Cactus 1549’, an Airbus A320 on a flight from New York City’s LaGuardia Airport to Charlotte, North Carolina, struck a flock of birds shortly after take-off, losing all engine power. Unable to reach any airport for an emergency landing, Captain Sullenberger and co-pilot Skiles glided the plane to a ditching in the Hudson River off Midtown Manhattan.

The captain and pilot in command was 57-year-old Chesley B. Sullenberger, a former fighter pilot who had been an airline pilot since leaving the United States Air Force in 1980.

At the time, he had logged 19,663 total flight hours, including 4,765 in an A320; he was also a glider pilot and expert on aviation safety.

First officer Jeffrey Skiles, 49, had accrued 20,727 career flight hours with 37 in an A320, but this was his first A320 assignment as pilot flying.

There were 150 passengers and three flight attendants and of course the two pilots.

All 155 people on board were rescued by nearby boats, with a few serious injuries.

The Flight and Bird Strike

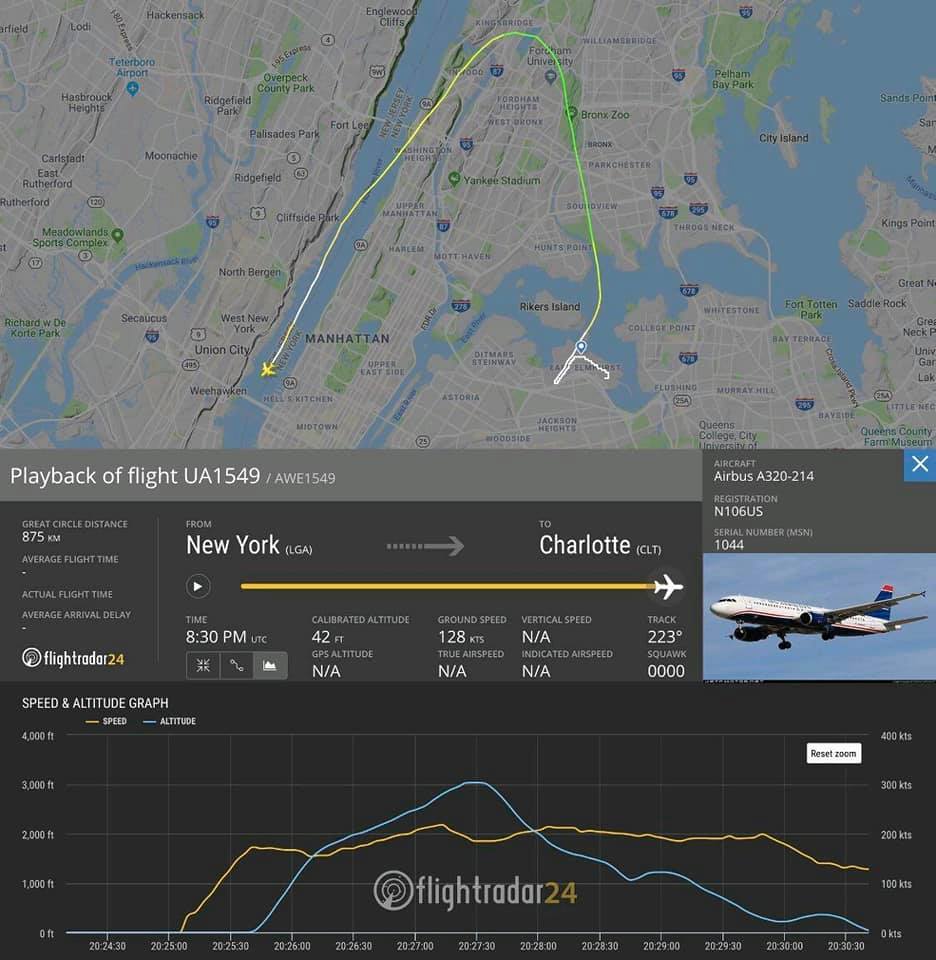

The flight was cleared for takeoff to the northeast from LaGuardia’s Runway 4 at 3:24:56 pm Eastern Standard Time (20:24:56 UTC). With Skiles in control, the crew made its first report after becoming airborne at 3:25:51 as being at 700 feet (210 m) and climbing.

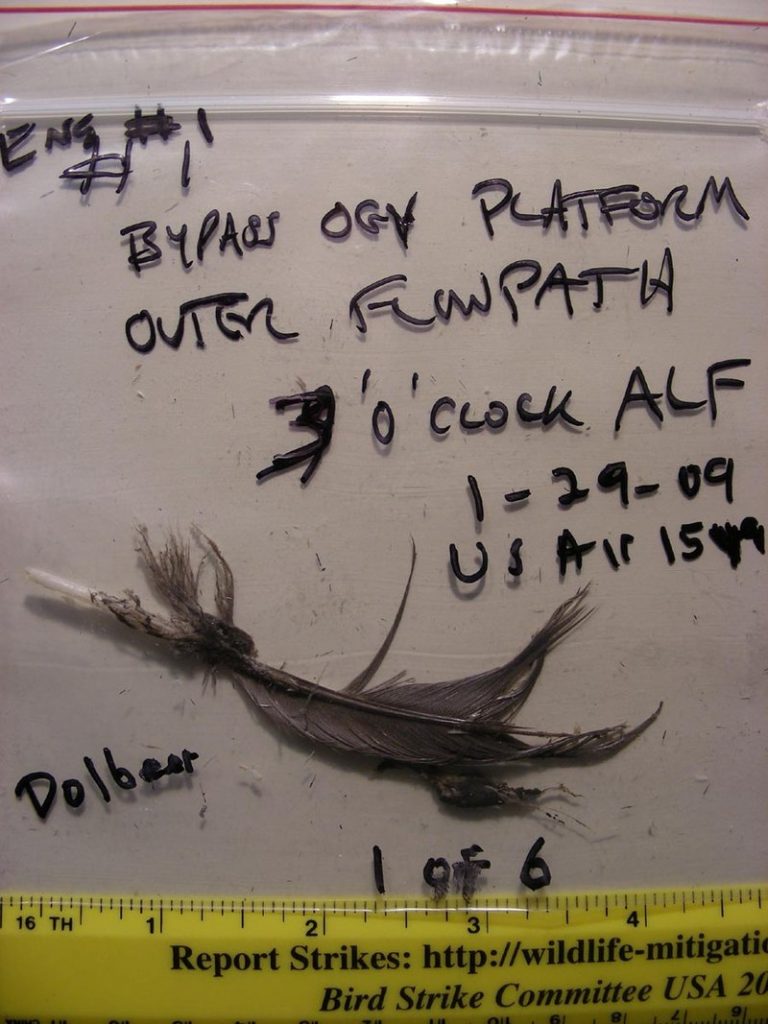

At 3:27:11 during climbout,, the plane struck a flock of Canada geese at an altitude of 2,818 feet (859 m) about 4.5 miles (7.2 km) north-northwest of LaGuardia.

The pilots’ view was filled with the large birds; passengers and crew heard very loud bangs and saw flames from the engines, followed by silence and an odour of fuel.

Both engines had shut down and Sullenberger took control while Skiles worked the checklist for engine restart. The aircraft slowed but continued to climb for a further 19 seconds, reaching about 3,060 feet (930 m) at an airspeed of about 185 knots (343 km/h; 213 mph), then began a glide descent, accelerating to 210 knots (390 km/h; 240 mph) at 3:28:10 as it descended through 1,650 feet (500 m).

Sullenberger radioed a mayday call toNew York Terminal Radar Approach Control (TRACON): “… this is Cactus 1539 [correct call sign was Cactus 1549], hit birds. We’ve lost thrust on both engines. We’re turning back towards LaGuardia”.Air traffic controller Patrick Harten told LaGuardia’s tower to hold all departures, and directed Sullenberger back to Runway 31. Sullenberger responded, “Unable”.

Sullenberger asked controllers for landing options in New Jersey, mentioning Teterboro Airport. Permission was given for Teterboro’s Runway 1, Sullenberger initially responded “Yes”, but then: “We can’t do it … We’re gonna be in the Hudson”.

The aircraft passed less than 900 feet (270 m) above the George Washington Bridge. Sullenberger commanded over the cabin address system, “Brace for impact’, and the flight attendants relayed the command to passengers.

Meanwhile, air traffic controllers asked the Coast Guard to caution vessels in the Hudson and ask them to prepare to assist with rescue.

About ninety seconds later, at 3:31 pm, the plane made an unpowered ditching, descending southwards at about 125 knots (140 mph; 230 km/h) into the middle of the North River section of the Hudson tidal estuary.

Flight attendants compared the ditching to a “hard landing” with “one impact, no bounce, then a gradual deceleration.

Sullenberger opened the cockpit door and gave the order to evacuate. The crew began evacuating the passengers through the four overwing window exits and into an inflatable slide /raft deployed from the front right passenger door.

Water was entering through a hole in the fuselage, through cargo doors that had come open, and from one of the rear doors that was opened.

As the water rose the attendant urged passengers to move forward by climbing over seats. One passenger was in a wheelchair.

Finally, Sullenberger walked the cabin twice to confirm it was empty.

Some evacuees waited for rescue knee-deep in water on the partially submerged slides, some wearing life vests. Others stood on the wings or, fearing an explosion, swam away from the plane.

One passenger, after helping with the evacuation, found the wing so crowded that he jumped into the river and swam to a boat.

The initial NTSB evaluation that the plane had lost thrust after a bird strike was confirmed by analysis of the cockpit voice and flight data recorders.

This water landing of a powerless jetliner became known as the “Miracle on the Hudson“, and a NTSB (National Transportation Safety Board) official described it as “the most successful ditching in aviation history”. The Board rejected the notion that the pilot could have avoided ditching by returning to LaGuardia or diverting to nearby Teterboro Airport.

The pilots and flight attendants were awarded the Master’s Medal of the Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators in recognition of their “heroic and unique aviation achievement”.

Footnote

Unlike most aircraft accidents, the wreckage was not scrapped, and was instead put on display for the public.

| Aircraft type | Airbus A320-214 |

| Operator | US Airways |

| IATA flight No. | US1549 |

| ICAO flight No. | AWE1549 |

| Call sign | CACTUS 1549 |

| Registration | N106US |

| Occupants | 155 |

| Passengers | 150 |

| Crew | 5 |

| Fatalities | 0 |

| Injuries | 100 |

| Survivors | 155 |