The struggle over the remains of SAA has taken an appalling twist.

Up to now I have held a grudging respect for the CAA’s commitment to uphold standards, whether ICAO SARPs, or its own regulations. I may have often disagreed with the methods and the lack of engagement with its subjects, yet the CAA has by and large maintained its integrity. Now however, the confidence that we can have in the regulator’s integrity has been broken.

The Department of Public Enterprises (DPE) has, against all standards of sanity, persisted in using SAA for a grotesque flag waving exercise. Beyond a public relations stunt, there can be no justification for pulling an SAA A340-600 out of mothballs and spending an estimated R5 million to fetch a pallet of vaccines.

In response to a torrent of criticism, the DPE has claimed that they were also carrying cargo northbound. Yet this is contradicted by the aircraft’s manifest, which shows just eight tons of spares for the plane were carried since they were operating into Brussels with no ground support. This is confirmed by the flight number which was preceded by a 4 which denotes a positioning flight, and not a 6, which is used for freight.

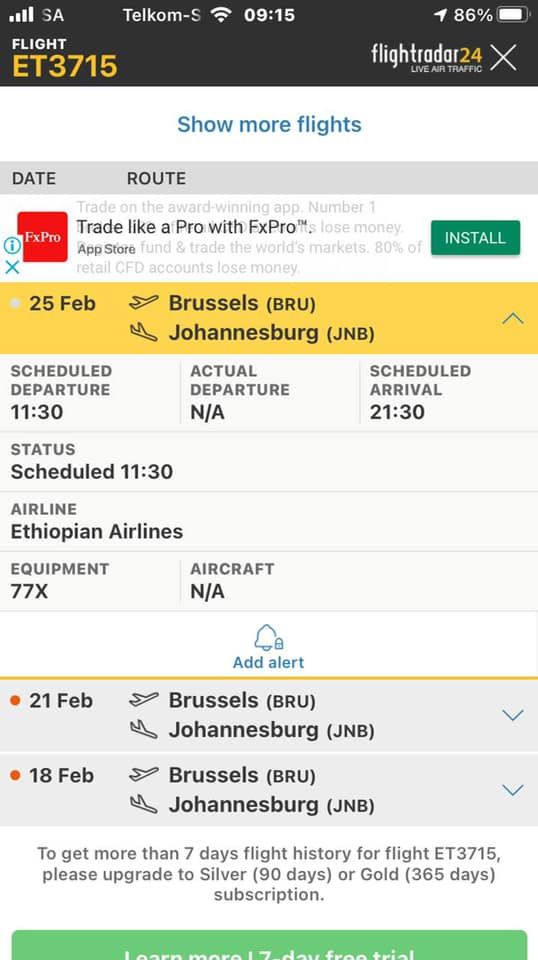

We are told the vaccines would fit in a bakkie and could easily be airfreighted – for a 100th of the cost. Emirates airfreighted ten times as many vaccines on a couple of pallets to Ghana in the belly of a scheduled B777. There was even an Ethiopian Airlines freighter operating from Brussels to Johannesburg that could have accommodated the pallet of vaccines. And they could have sent the Presidential Boeing Business jet – or even one of the Falcons.

Apart from the waste of public resources, and SAA being beyond bankrupt, the government bent basic aviation rules to send an empty A340-600 to Brussels. This despite not paid the vast majority of the pilots for 10 months and refusing to pay their death cover unless the pilots agree to a settlement agreement.

For the aviation industry, the surprising victim in this mix is the CAA, and its hitherto largely unblemished efforts in maintaining aviation safety. It is inescapable that, given the pressures from the DPE to show that SAA can operate (with only black pilots), rules wer bent and perhaps broken to enable this obscenely expensive public relations stunt.

This farce began in the middle of February when a consignment of vaccines needed to be shipped to South Africa. Seeing an opportunity to show how the new SAA would be vital to the country, the DPE was desperate to use the flight as a public relations exercise. This meant sending an huge A340-600 from Johannesburg to Brussels empty – to bring back the single pallet. It’s estimated that in fuel alone this would burn 200 tons, or approximately R2 million.

However, the airline has essentially been grounded since March 2020, which means that its pilots are far from able to meet recency requirements. In addition, the SAA organisational structure has been eviscerated of key staff members and the postholders required by the CAA.

Embarrassing for the DPE, the first attempt to launch the A340 to Brussels was stopped by an SAA manager, who no doubt politely pointed out that the basic requirements to operate the flight were not in place.

SAA must have been so confident it would be able to secure CAA approval that it had fuelled the aircraft for the flight. But this made it too heavy to tow, so the A340 sat out in the rain while the bureaucrats wrangled.

To its great credit the CAA stood its ground until eventually the flight was cancelled. As a critical observer of the CAA, I congratulated the regulator on winning a showdown against what must have been enormous political pressure.

Eventually a TUI Boeing 787 was chartered and when the vaccines arrived in we dared hope that this would be the end of this unfortunate skirmish. However, as the dust began to settle, a worrying sign that all was not well behind the scenes emerged. The CAA published a letter saying that it had approved all the requirements for the first flight; just that it taken a little longer than hoped. This was an obvious face-saving attempt to repair relations with the DPE and the airline.

The vaccines could easily have been loaded onto a scheduled cargo flight – for less than a 100th of the cost.

The DPE makes its ‘Use SAA regardless of cost” aim clear.

However, if SAA could not fly, the government’s “save SAA at all costs” policy was at risk of being shown to be unworkable. Another small load of vaccines was ready for delivery, so undeterred, the DPE tried again to use SAA.

Raising the airline from the dead is a tough task. There were over 100 regulatory hurdles that had to be overcome before the flight could be signed off. These hurdles included the airline not having: A CEO, or a flight operations dispatch capability, no flight technical and safety department, operations control centre, recurrency training program or even up-to-date Jepp charts and Airbus FlySmart Apps.

Simply put, the remains of SAA no longer met the structure required by the CAA. Furthermore, many technical requirements were not addressed in the approval letter: specifically, whether SAA could have a valid AOC, or EASA approval if it was not operating.

The difficulties of meeting these requirements should have been a showstopper. But proving that the cost of justifying SAA is limitless, the CAA was given clear instructions that it had to make it happen. On 16 February a more detailed explanation was released by the CAA’s heads of legal compliance, confirming that no less than 13 exemptions to the safety requirements had been granted. The CAA tried to limit its exposure by granting the exemptions for one flight only.

Most other airlines around the world have invested in keeping their pilots current and proficient. However SAA decided to use an ATO that was not properly certified for the operations that SAA requires. The flying school in question belongs to a black SAA pilot, and was reportedly paid over R100,000 for the training. It appears the Public Finance Management Act (PFMA) was ignored.

The real question that arises is about pilot currency and qualifications. One of the biggest hurdles was that there were no SAA examiners for the pilots’ proficiency tests as they are all SAAPA members and were locked-out, without pay.

It is believed that the flight was dispatched with the crew lacking critical currency requirements, particularly with regard to their ability to fly Category 3 instrument landings. What would happen if the Brussels’ winter weather required a Cat 3 ILS approach – or a GNSS PBN approach? Because the pilots lacked full currency, it’s hard to believe that they could have been considered safe or even proficient in these extremely demanding skills, which require regular practice and professional checks. If Brussels and their Alternative was Cat 3, what would they have done – flown around until their fuel ran out?

To issue 13 exemptions is an appalling dereliction of safety and sanity

When Jim Davis writes his accident reviews, he often asks the question; “Would I have been happy to be a passenger in that plane?” With 13 exemptions granted for the Brussels flight, the answer to this question is a resounding ‘NO’. Having 13 exemptions makes a highway through James Reason’s Swiss cheese model.

This is a dangerous abuse of power by the DPE. It is also bodes ill for the future of aviation that the CAA allowed its hitherto inviolate standards to be so obviously compromised. To issue one exemption should be an exception.

To issue 13 exemptions is an appalling dereliction of safety and sanity. I cannot imagine what EASA thought when they saw this A340-600 heading into their airspace with no less than 13 exemption flags pinned to its flight clearances.

SAA, with the collusion of the CAA, launched a flight far below safety standards

And so, late on Wednesday night 24 February, SAA, with the collusion of the CAA, launched a flight that was far below any usual acceptable safety standards. For one brief moment there was hope that it may not fly after all when the plane sat on the ground, reportedly because its radar was unserviceable. But in the end the political imperative triumphed, and the 340 took off after midnight, as flight SAA4272.

What makes the travesty of the flight particularly egregious is that SAA does not have the money to pay just the risk premiums on its pilots’ Group Life insurance. I am told that four pilots have already died tragically in 2021, one of Covid-19, and without premiums, the insurer may well decline to pay the benefits.

From the regulator’s past history of run-ins with CemAir, I am confident that these exemptions would not have been the case for any other privately owned airline. We have seen all the other airlines grounded for smaller problems than the 13 exemptions required for this flight.

Thus does politics push us ever faster down the slippery slope towards failure – first the airline – then the aviation industry – then the whole state.