ENABLEING INTRA AFRICAN TRADE AND TOURISM

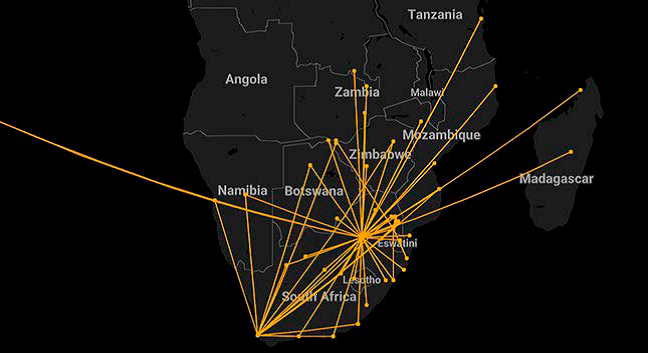

Airlink is rapidly growing into the role of key enabler of air connectivity across southern Africa.

BY PROVIDING regional Intra-African links to relatively unserved regional centres, Airlink is providing essential connectivity to enable the development of Intra-African trade and tourism that is essential for the continent’s economic growth.

In just the past few months, Airlink has vigorously expanded its route network and the number of flights and thus seats available to Walvis Bay, Maputo and Lubumbashi.

“Since launching services linking Johannesburg with Maputo and with Lubumbashi last October and November respectively, we have seen a steady increase in passenger traffic on those two routes. This reflects an uptick in trade and economic activity between South Africa, Mozambique and the D.R Congo. By increasing our schedule on these routes we will cater to the increased demand while providing more choices to customers wanting to travel to destinations across South Africa and throughout Southern Africa,” says Airlink CEO and Managing Director, Rodger Foster.

The importance of Airlink opening up feeder routes such as these cannot be overstated. One of the key challenges faced by the African air transport industry is that it is fragmented, due to almost all of the 53 African states owning their own airlines. Africa covers 30 million square km, (including adjacent islands, mostly Madagascar). To succeed in opening up these underserved and protected routes requires fortitude and patient negotiation with the many African states that wish to protect their own airlines – even when they are not operating.

‘Airlink has quietly persevered’

In this regard Airlink’s opening up of the Johannesburg – Windhoek and Cape Town – Walvis Bay routes are notable victories for African economic growth. In both instances the market needed the airlift capacity. In the former it took Airlink several years to wrestle a dormant designation away from a protected competitor in order to activate traffic rights, and in the latter the absence of a hibernating airline that previously operated the route was flagged by the Namibian Airports Company, which called on Airlink with a positive collaborative outcome.

There are other examples of where working together yields results, such as Airlink’s close cooperation with IACM in Mozambique and CAAZ in Zimbabwe, and this highlights the important role of privately owned airlines in sustainably operating these regional routes and contributing to achieving the “Single African Air Transportation Market”.

Each nation’s respective civil aviation authority (CAA) has oversight responsibility for their aviation sector. However often regulatory oversight includes over protection as the regulator is also the owner of infrastructure such as airports and ground handling, and it may often be seen to be favouring the national airline, even if it is moribund. Thus, when an efficient and privately owned competitor such as Airlink wishes to expand into a new regional destination, it often has to pay extremely high ground handling charges – in some cases more than ten times greater that the local state-owned airline pays. Frequently the national airline pays fees in local currency and the competitor has to pay in US dollars.

There is also evidence that civil aviation regulators impose what are deemed to be excessive or questionable bureaucratic restrictions on the industry, particularly in the granting of licences, rights and aircraft operators certificates, and this further deters investors.

The anti-competitive approach of governments to protect their state owned airlines is compounded by the way in which the current transport patterns mitigate against the development of Intra African trade. Economic geographers have described the colonial road and railroad system as ‘dendritic’ – which is a leaflike vein pattern originating from the main outlets of international trade into the African interior with few if any links between the interior region. As a consequence of the dendritic transport pattern, almost no railways were built to move goods or people intra-Africa; that is between and within states inside Africa. Almost all colonial transport links were built from the interior to the port, primarily for the then purpose of exporting raw materials to the colonial power.

This vein-like transport pattern hampers intra-African transport and makes trade between countries in Africa very difficult. Often the only way to get from a mid-size town in one country to another mid-size town in a different country is to travel overland to the capital city, often on rough roads. These capital cities are usually located on or near the coast, and from there one flies to the next capital city and again travels on bad roads to get to the secondary city.

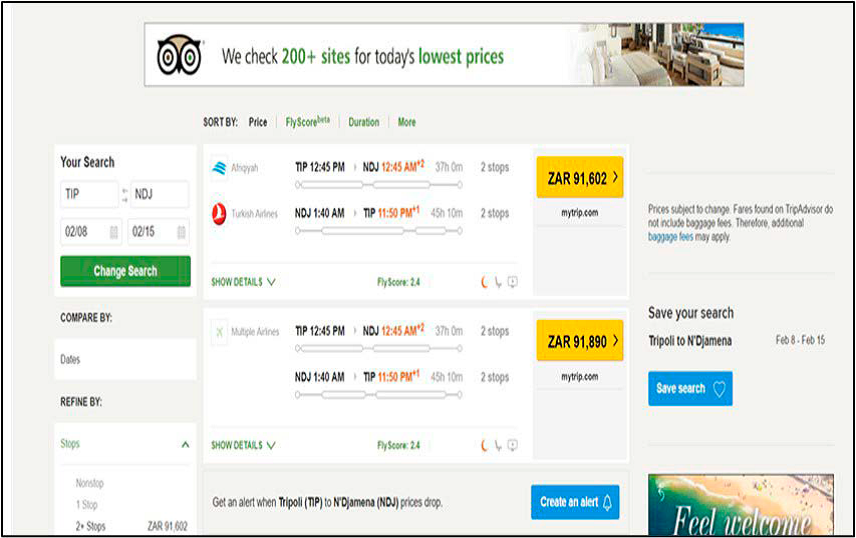

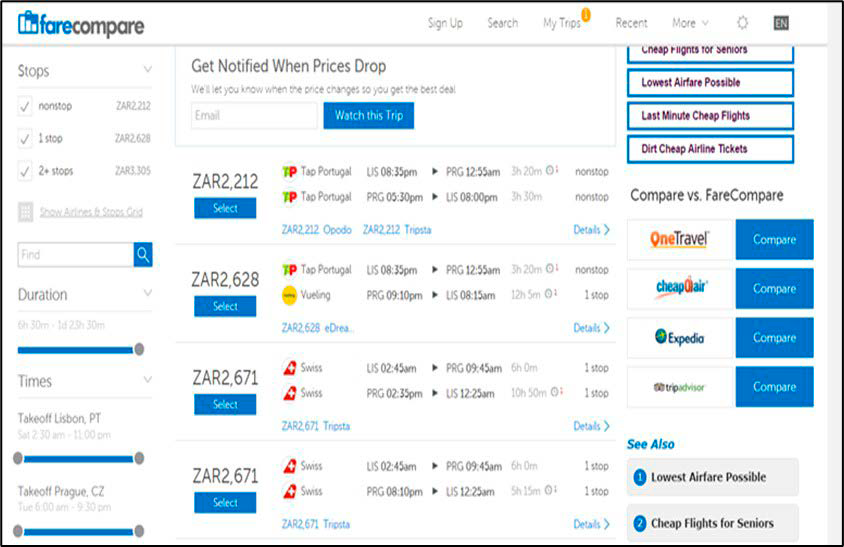

To show how poor African air connectivity is, a Google search for flights between the two cities of Tripoli and N’Djamena, which are 2281 km apart, showed that the quickest route took 37 hours and cost a staggering R91,602.

‘its ability to negotiate and mobilise bilateral agreements’

In comparison, Lisbon to Prague, which is slightly further at 2,300 km, costs one fortieth the price and takes one tenth of the time.

Despite this massive failure of the airline industry to provide affordable and frequent flights, the transportation challenges caused by political differences and requirements between countries have grown since the end of the colonial era. Many African states protect their airlines by restricting airline connectivity using bilateral agreements and the ‘Freedoms of the Air’ to limit foreign carriers.

It is its ability to negotiate and mobilise bilateral agreements and the Freedoms of the Air that has made Airlink a particularly valuable part of the broader southern African transport infrastructure.

Before an airline can operate international services to another country, the governments negotiate a bilateral air services (bilateral) agreement. Bilaterals provide for traffic rights in terms of the routes airlines can operate; capacity, in terms of the number of flights and passengers; specific airlines permitted to operate the routes; the ownership criteria of the airlines, which generally limits non-resident ownership; conditions regarding safety and security; and ticket prices. Many Air Services Licencing Councils (ASLCs) and Bilateral Agreements require airlines to submit ticket prices for approval.

The Chicago Convention established the rules under which international aviation operates. It also established the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the United Nations organisation responsible for fostering the planning and development of international air transport.

Bilaterals are now used to define the removal of restrictions on routes, capacity, and airline ownership. In the past ten or so years, many other airlines that had hoped to benefit from Africa’s oft-stated commitment to ‘Open Skies and air route liberalisation have fallen by the wayside, yet Airlink has quietly persevered and thus has found itself very well positioned to take advantage of the vacuum in air services created by the Covid pandemic.