(Yolanda Mackay, Director; Norton Rose Fulbright)

A deep dive into international aviation law and precedent shows that airlines may be liable if a passenger gets infected by Covid-19 on a flight.

This article explores the extent to which carriers may be considered guarantors of the safety of their passengers and how the law classifies contamination that is proven to have occurred on board an aircraft.

The article will further delve into whether the law classifies COVID 19 as an “accident” in terms of Article 17 of the Warsaw Conventions and the Montreal Agreement and whether air carriers may be held liable for contamination associated with a flight.

First, some background definitions:

Article 17

Article 17 of the Warsaw Conventions and the Montreal Agreement impose strict liability on carriers for damage sustained in the event of the death or wounding of a passenger or any other bodily injury suffered by a passenger that is caused by an accident and the injury so sustained took place on board the aircraft or in the course of any of the operations of embarking or disembarking.

Article 14 of the Chicago Convention

The 1944 Convention on International Civil Aviation (the Chicago Convention), recognises plague and other communicable diseases such as cholera, typhus (epidemic), smallpox, yellow fever, and ratifying States must specifically take steps to prevent these diseases from spreading by means of air transportation. The Chicago Convention makes it mandatory for air carriers to comply with the pertinent provisions of the International Health Regulations (2005) of the WHO.

Under Article 14 of the Chicago Convention each contracting state is required to take effective measures to prevent the spread of communicable diseases and to keep in close consultation with those international agencies concerned with international regulations relating to sanitary measures applicable to aircrafts.

Accident

Both conventions require an “accident” to have caused the illness and to have taken place on board the aircraft or in the course of the operation of embarking and disembarking.

An “accident” has been defined as an unusual or unexpected event that is external to the passenger, and which results in physical injury to the passenger. Bodily injury includes the “physical infliction of physical injury during the flight even though not already manifested at the time of the conclusion of the flight, for example a disease or illness contracted upon the aircraft (resulting from) food (contamination)” as defined in Air France v. Saks, 470 U.S. 392 (1985).

In the ‘Crash at Little Rock, Arkansas 231 E.D. Ark. (2002)’, the court broadened the scope of the interpretation of the Convention and confirmed that a party can claim for mental and psychological injuries to the extent that they are caused by and approximately flow from the physical injury caused by the accident.

Thus a claimant must prove that an “accident” occurred within the meaning of Article 17 in order to succeed with a claim for liability against a carrier.

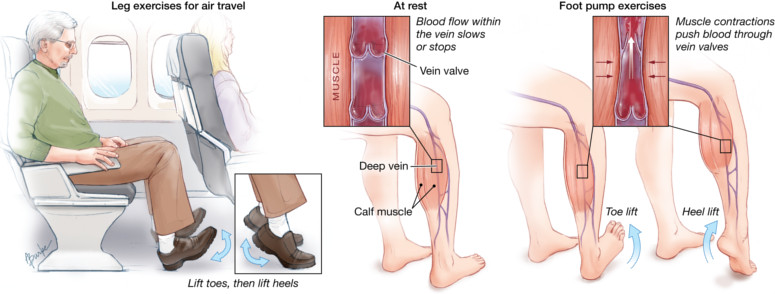

Deep Vein Thrombosis

A form of injury that has been associated with air carriage is the deep vein thrombosis (DVT) which is a serious condition that occurs when a blood clot forms in a vein located deep inside the body.

The aviation industry has seen a number of claims associated with DVT. However, current medical studies have not proven that air transportation increases the risk of developing DVT and this is a topic currently being researched by the World Health Organisation.

The point of contention facing air carries concerned with DVT litigation is whether the condition can be classified as an “accident” in terms of Article 17 of the Warsaw Convention. A claimant must provide any admissible evidence that he developed DVT as a result of an unexpected or unusual event or happening external to the passenger.

In Blanset v. Continental Airlines 204 S.D. Tex. (2002) a passenger developed DVT and instituted proceedings against Continental Airline for alleged injuries sustained while on board the carrier. The claimants alleged that the carrier failed to warn them of the risk of developing DVT during air transportation and failed to take adequate precaution to inform the claimants of the risk of developing DVT.

The claimants alleged that the defendant violated a custom or procedure amongst international air carriers by failing to warn passengers of contracting DVT on board an aircraft and that this could lead to an “accident” within the meaning of Article 17 of the Warsaw Convention.

Continental Airlines then moved to dismiss this claim on the basis that developing DVT was not an “accident” under Article 17. Continental was unsuccessful in its attempt. The court held that a failure to carry out established routine procedures can be an “accident”.

However, the court left open the question of whether warning passengers about the risk of DVT specifically is an established custom or procedure within the aviation industry.

In Air France v. Saks, 470 U.S. 392 (1985) the court held:

“If… nothing happens during an ordinary or unremarkable flight that involves the actions of anyone except for the passenger himself or herself and his or her atypical reaction to a normal and unremarkable flight, there had been no unexpected or unusual event or happening. The only basis upon which liability could arise in such circumstances would be for a court to hold that a culpable act or omission is always an unusual or unexpected event or happening, so that wherever negligence is established, or known risks are ignored, an “accident” must have occurred. But that ignores the fact that the culpable act or omission cannot necessarily be described as an unusual event or happening in itself.”

The questions to ask are:

- Is there an accident as required by the Conventions;

- Is there admissible evidence of the occurrence of the accident;

- Is there an awareness of a risk; and

- Did the carrier warn passengers of established routine procedures or provide necessary information relating to the risk.

Case law reveals that while not advising passengers of the risk associated with DVT a carrier may be held as negligent, this negligence is not in itself an accident within the meaning of Article 17 in that DVT sustained by a passenger is not linked to an unusual and unexpected event external to them as a passenger.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) is a contagious and sometimes fatal respiratory illness that has been the subject of litigation for air carriers.

In May 2003, the WHO issued an Emergency Travel Advisory to passengers and airlines advising that, while there was a low in-flight transmission rate of passengers, parties should be alert to the symptoms associated with SARS. Recommendations were set-out to restrict travel and minimise in-flight transmissions.

A Scottish decision, King v Bristow Helicopters 2001 SLT 126, confirmed that the bodily injury induced by an accident in terms of the Convention does not have to manifest during or at the conclusion of the flight as it is sufficient for the injury, illness or disease to have been contracted upon the aircraft through the contamination of the aircraft’s air supply.

Similar to DVT liability claims, the Conventions require an “accident” to have caused the damage to take place on board the aircraft or in the course of operation of embarking or disembarking. The current litigation on DVT will further assist in determining whether an airline’s failure to warn passengers of SARS and/or to take steps to isolate a passenger with SARS symptoms or honour requests by other passengers for alternative seating might possibly amount to an accident as an unexpected or unusual event or happening.

COVID-19

Locating or tracing of passengers after flights to enable airlines to ascertain those likely exposed to risk is complicated as passengers on disembarkation would have dispersed widely. In the projected two to fourteen days’ incubation period before the COVID-19 may fully manifest, the airline should ensure that they have sufficient and correct data of passengers to give to airline medical staff and health authorities.

In the 21st century, however, technology has played a major role in enhancing contact tracing of communicable virus such as COVID 19, presenting individualised tracking as a reliable way to trace the movement of individuals who are infected and to identify individuals with whom the former came into contact during the period in which they were contagious. Mobile location data has been proposed as a helpful method to identify potentially exposed individuals as some governments and the private sector have heavily relied on data-driven technologies to help contain the novel COVID 19.

Thus technological measures have become a critical solution for contact tracing, quarantine enforcement, tracking the spread of the virus, and allocating medical resources. However, these practices raise significant human rights concerns as measures taken that limit people’s rights and freedoms must be lawful, necessary, and proportionate.

The airlines’ legal duty thus appears to be limited to collaborating with contracting states to determine whether any passenger’s condition poses a direct threat to public safety relying on directives issued by public health authorities.

Carriers must comply with international health regulations and the laws of the countries to and from which they operate services. If they ignore passengers who look unwell or present symptoms, they may be exposed to penalties.

In Dias v. Transbrasil Airlines, Inc., 26 Av. Cas. (CCH) 16,048 (S.D.N.Y. 1998). the court ruled that the poor cabin air quality due to the aircraft’s air filtration system not working properly which resulted in an injury to the passenger constituted an “accident”. Thus emphasising the strict obligation that air carries owe to passengers and their safety.

When determining whether a carrier may be held liable for the possible transmission of COVID 19 on-board, WHO examines the following risk factors:

- Did the carrier deny a passenger check-in boarding who has COVID 19 symptoms or take any precautionary steps to check that the passenger is medically fit to fly?

- Did the carrier isolate a passenger who exhibited COVID 19 symptoms during the flight or await on medical authorities at destination before disembarking passengers?

- Did the carrier trace fellow passengers where it was notified that a passenger on one of its flights had COVID 19?

- Was there a failure in the cabin ventilation system? or

- Was there a failure to follow prescribed regulatory protocols to screen passengers when boarding or other precautions required?

World Health Organisation (WHO)

The International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) works closely with WHO and other international health and aviation bodies to assist in containing the spread of communicable disease in aviation. The ICAO has developed Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs) to ensure a coordinated response.

The aviation sector’s primary role is to minimise travel of individuals who have contracted a communicable disease to other jurisdictions through passenger screening procedures. These procedures are performed at airports and through the presentation of health certificates or the famous ‘yellow card’ indicating vaccinations against certain communicable diseases where mandated.

Burden of Proof

The burden of proof rests with the claimant to prove that they suffered an illness as a result of contamination on the carrier. Since the source of contamination of COVID 19 has been proven to be nearly impossible to trace, more so that such manifestation of the contamination occurred during a flight, it will be difficult for a claimant to prove that the occurrence of an accident within the definition of Article 17.

It is both a legal and factual question whether passengers will be successful in claims for the contamination of COVID-19 aboard a flight and whether, as with DVT, issues will arise as to what is an accident – as the event itself must be the cause of the accident rather than the illness.

Article 20(1) of the Warsaw Convention states that the carrier is not liable if they can prove that they and their agents have taken all necessary measures to avoid the damage or that it was impossible for either party to take such measures. The Montreal Convention adopted this defence but changed the wording.

Article 21(2) of the Montreal Convention states that the carrier is not liable for damages arising under Article 17 to the extent that:

- such damage was not due to the negligence or other wrongful act or omission of the carrier or its servants or agents; or

- such damage was solely due to the negligence or other wrongful act or omission of a third party.

Notably, even in circumstances where a passenger is able to prove that they contracted COVID-19 on board an aircraft or while embarking or disembarking, the passenger’s claim may be limited by the limits often highlighted in the contract of carriage, and terms contained on the air ticket.

Voluntary assumption of risk

Where an air carrier has taken all necessary precautionary measure to mitigate infections, Article 20 of the Montreal Convention provides a defence, where the Air Carrier proves that the damage was caused or contributed to by the negligence or other wrongful act or omission of the person claiming compensation.

The defence of voluntary assumption of risk is based on the concept that no wrong can be done to one who consents. Consequently, where a passenger is deemed to have agreed to assume all the inherent risks involved with flying aboard an aircraft during a pandemic, the air carrier may be absolved of the responsibility for injuries arising from flying in an aircraft that did not result in an accident from the act or omission of the carrier.

Where a passenger decides not to heed the advice against traveling and by so doing, contracts the COVID-19 on board an aircraft, either before or during embarking or disembarking the aircraft, the express or implied agreement by the passenger to assume both the physical and legal risk may absolve the airline from all future liability claims that may be made by the passenger provided the carrier is not negligent.

It must be noted that the principle of “voluntary assumption of risk” falls solely under the Montreal Convention and not the Warsaw Convention. The Warsaw Convention does not limit liability for passengers against air carriers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a passenger may be successful in pursuing a claim for liability against an air carrier for contracting Covid-19 on board the aircraft if they can prove negligence (“accident”) on the part of the carrier or their agents or sub-contractors.

However, where the air carriers have taken all reasonable measures by complying with all the prescribed health procedures and where a passenger is infected by a fellow passenger who has Covid-19 but is asymptomatic, the passenger would not be able to sustain a claim that the air carrier is liable for the transmission of Covid-19 to the claimant.

The air carrier may also be absolved from all liability on the basis that passengers, who contracted Covid-19 on board an aircraft, voluntarily assumed the physical and legal risks, whether expressly or impliedly, in boarding a flight during the well-publicised risks of the pandemic.