(STEVE TRICHARD) – By the end of World War 1, aerial operations had made an impact across all forms of warfare. The majority of air power roles and missions were operational, if not thoroughly tested. However, air transport was the very last role to emerge and mature, since contemporary technology could not meet the requirement.

AT THE BEGINNING OF WORLD War 2, no military activity could ignore the third dimension. Hard-earned experience confirmed the fundamental characteristics of air power in the minds of all military planners: speed, height, reach, ubiquity and flexibility.

Transport aircraft became a high-value asset during WWII. To satisfy the high demand, existing civilian air transport designs were modified as freighters and military transport aircraft. The Douglas DC-3 airliner became the hugely successful military transport C-47 Skytrain and C-53 Skytrooper. More than 16,000 DC-3 variants were built.

Loading these aircraft were time-consuming. The tail wheel and side door designs made cargo handling problematic. The search for a military transport aircraft began in all earnest. This led to aircraft purpose-built to move troops and heavy, bulky loads to semi-prepared airstrips with little or no ground support.

The Ar 232’s landing gear could “kneel”

Design features that are considered essential for modern cargo aircraft are a high wing, a box-shaped fuselage, with the main undercarriage accommodated in sponsons on the sides of the fuselage, a high tail with an integrated ramp and turboprop engines in, or flush under, the wings. Furthermore, it must be able to operate from austere airfields.

The DNA of the military transport aircraft can be traced through four aircraft that were products of exceptional innovations and ground-breaking designs. These aircraft are the Junkers Ju 90, Arado Ar 232, Fairchild C-123 Provider and the Lockheed C-130A.

When the Junkers Ju 89 long-range bomber programme was abandoned, the third prototype was, at the request of “Deutsche Luft Hansa”, rebuilt as an airliner with a wider passenger-carrying fuselage. The new design was designated the Ju 90 and made its maiden flight in August 1937.

It was a taildragger with four engines mounted on a low wing. Anybody that ever walked in a parked Dakota DC-3 will know that getting from the tail to the cockpit is uphill and not conducive to loading the aircraft.

One crucial innovation for cargo aircraft was thus introduced in 1939 on Ju 90 V5. For easier loading of passengers and cargo, the concept of the “trapoklappe” was formulated. The “trapoklappe” boarding ramp, when lowered, raised the fuselage to the horizontal position and in doing so levelled the floor. Vehicles could be “wheeled” into the aircraft, and the ramp incorporated a personnel stairway. The Ju 90 evolved into the Ju 290, the first operational military aircraft with a ramp.

We have to divert slightly from military air transport to discuss the production type Ju 90 A-1 (the airliner) in some detail because South African Airways (SAA) ordered two of these aircraft.

Junkers Ju 90 V1

The Ju 90 A-1 had a range of 1 300 km at a cruise speed of 170 knots. The maximum passenger capacity was 40. The cabin was divided into five passenger compartments, each containing eight seats. The seat layout was four seats on either side of a central aisle. The four seats were paired and facing each other. Two toilets and a cloakroom were in the rear of the aircraft. The baggage hold was forward of the passenger compartments. The fuselage interior width was 2,83m, larger than the present-day Embraer 195 width of 2,74m. The loading ramp was not fitted to the A-1.

SAA ordered two A-1s with Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp engines. These were known by the alternative designation Z-3 to distinguish them from the BMW-powered Z-2.

The two Junkers Ju 90 A/Z-3 (as referred to on the hugojunkers website) aircraft were assigned the South African Civil Aircraft Registration numbers of ZS-ANG and ZS-ANH. In the register, the type is indicated as Junkers Ju 90 B-1.

Neither of these aircraft was delivered to SAA due to the start of WWII. They were delivered to the Luftwaffe and were destroyed early in the war.

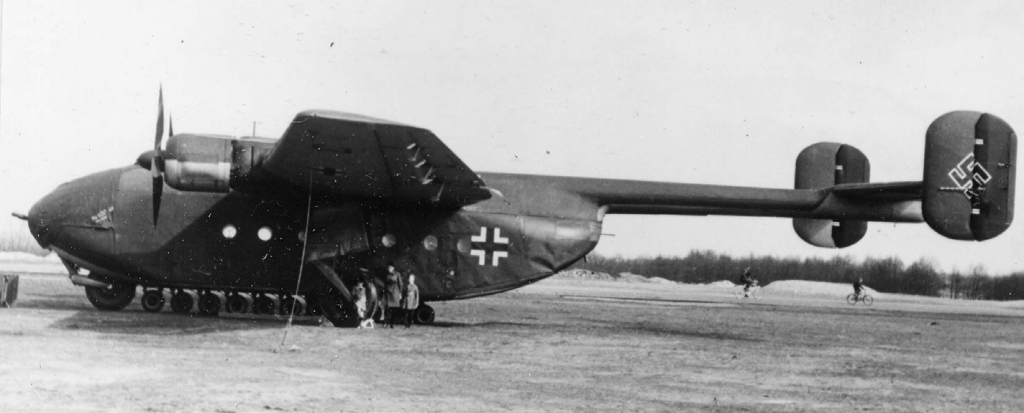

Arado Ar 232

In late 1940, the German Ministry of Aviation requested designs for an “all-terrain transporter for use near the front”. The requirement called for a tactical aircraft with a rear-loading design, which could operate from “unprepared terrain”.

Arado Flugzeugwerke’s design was selected, and the result was the Arado Ar 232, the first purpose-built cargo aircraft. Arado’s development team, headed by Wilhelm van Nes, faced two main challenges. Firstly, to minimise the time spent in the loading and unloading without ground support, and secondly, to design an aircraft to cope with operations on extremely rough terrain.

The Ar 232 design directly addressed the loading and unloading issues of contemporary aircraft. The cargo hold was a box-shaped design, with a winch installed in the roof. A hydraulically operated door was installed at the rear of the fuselage. The door consisted of two parts. The upper half hinged towards the ceiling, and the bottom part hinged downwards onto the ground, forming the loading ramp.

The high wings allowed the cargo hold to be closer to the ground and eased movement next to the aircraft. The high mounted tail boom cleared the area behind the aircraft allowing vehicles to drive up to the loading ramp. Small vehicles could be wheeled into the cargo hold via the ramp.

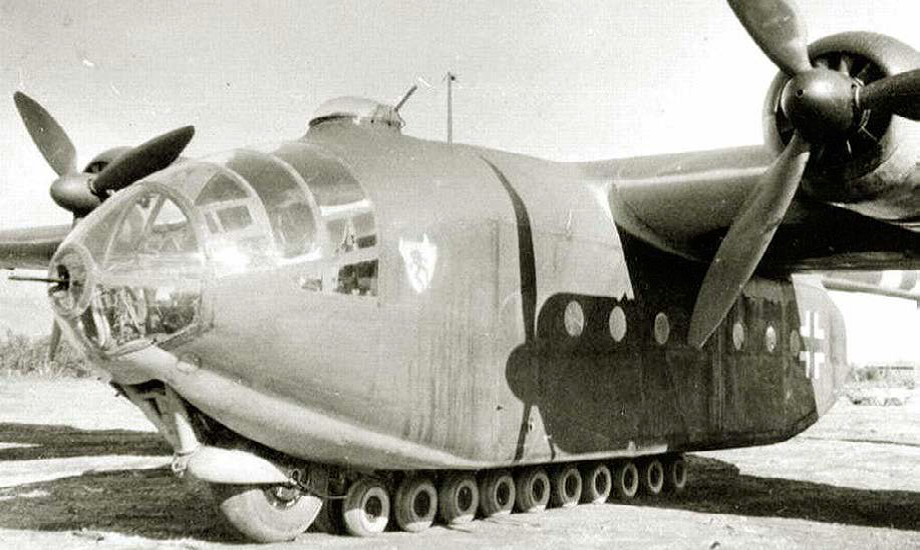

The Ar 232’s landing gear could “kneel”, i.e. lower the fuselage for more effortless loading.

It was the blueprint for features now considered to be standard for military transport aircraft, with two noticeable differences. The main undercarriage was still centred in the wing, while the ramp and tail configuration were not integrated.

The Ar 232’s ability to operate on extremely rough terrain must be briefly discussed. “Unprepared terrain” was defined in the requirement as a terrain with trenches 1,5 m wide, embankments of sand and rubble of maximum 80 cm high and fallen tree trunks up to 15 cm in diameter!

The Arado design team focussed on reducing the approach and takeoff speeds to minimise ground rolls and to develop extremely robust landing gear. The takeoff and landing speeds were reduced significantly through the Arado designed ‘landing flap’. It consisted of double-slotted Fowler flaps on the entire trailing edge of the wings. The ailerons extended with the flaps while retaining their function. The wing area increased by 25% and the Ar 232-A (twin-engined), at maximum takeoff weight (MTOW), could get airborne within 200 metres. The payload for the Ar 232-A was 2,500 kg, and for the 4-engined Ar 232-B payload was 4,700 kg.

The takeoff distance was further reduced by using jettisonable rocket propulsion units. The same method, referred to as JATO (Jet-Assisted Take Off) was demonstrated during the Lockheed-Martin C-130 airshow that formed part of the U.S. Navy “Blue Angels” formation displays.

Arado fitted and tested a boundary layer control system on one of the prototypes. The design team went as far as using rocket units and a brake parachute, installed in the tail, to shorten the landing run.

The unusual landing gear of the Ar 232 featured a conventional retractable tricycle undercarriage with a row of smaller non-retractable tandem wheel sets (bogeys) along the underside of the fuselage. The appearance of the row of small wheels led to the nickname “Tausendfussler” (millipede).

During takeoff from a prepared runway, the landing gear was fully extended. In flight, the main landing gear fully retracted inwards into the wings. The nose wheel retracted until it reached the same height as the bogeys and was still exposed.

For loading purposes, the aircraft was lowered by hydraulically shortening the main landing gear and retracting the nose wheel, with the aircraft settling onto the bogeys.

The same landing gear configuration was used for operations from unprepared surfaces.

The Ar 232 had another kneeling trick up its sleeve, by extending the nose wheel while in the loading configuration, the fuselage tilted rearwards, lowering the ramp even closer to the ground.

On 13 June 1944 an Ar 232 piloted by Paul Bader demonstrated the ability to meet the “unprepared terrain” requirements set four years earlier. A test track was prepared with trenches 1,5 m wide and sand embankments of 80 cm high. High-ranking officials attended the demonstration. Independent technicians that watched the flying display as guests believed that the extreme shocks that the aircraft endured caused damage to the airframe.

“The features for military transport were now reaching maturity”

Chase XG -20

The Chase XG-20 was an assault glider developed immediately after WWII by the Chase Aircraft Company for the USAF, built entirely of metal. With a wingspan of almost 34 m and an AUW of 31,751 kg, it was the largest glider ever built in the United States.

The XG-20 introduced design innovations with the main landing gear mounted in the fuselage and a high tail configuration with an integrated loading ramp. The airframe layout and features for military transport were now reaching maturity.

The XG-20 did not enter production. However, two radial engines were integrated into the airframe, evolving into the Chase C-123 AVITRUC. Chase began manufacturing the C-123 in 1953, but the contract was transferred to Fairchild due to a corruption scandal.

Fairchild C-123 Provider

The Fairchild C-123 Provider saw extensive service during the Vietnam War as a short-range assault transport used for airlifting troops and cargo to and from small, unprepared airstrips.

Unfortunately, the C-123 is perhaps best known for spraying “Agent Orange”, a herbicide used to defoliate parts of South Vietnam.

Lockheed C-130A

The American aircraft company Lockheed responded to a requirement from the USAF in 1951. The requirement was, in layman’s terms, for “a medium transport that can land on unimproved ground, be extremely rugged, be primarily for freight about 30,000 pounds for 1,500 miles.”

Willis Hawkins, head of the Lockheed design team, responded with a design that was to become the C-130 Hercules. The design had a similar layout to the C-123 Provider, with two noticeable design differences. The main wheels retracted into fuselage sponsons that did not intrude into the cargo hold, and it used four Allison T56 turboprop engines.

The Allison T56 turboprop engine weighed 794 kg and delivered 2,796 kW of power. In comparison, the largest radial engine ever mass produced was the 2,600 kW Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major at a weight of 1 585 kg. The T56 was developed specifically for the C-130 and was the final piece in search of the modern military transport aircraft.

The other engineering innovations on the C-130 were more than skin deep. The Allison engines generated sufficient power to allow the engineers to incorporate pressurisation into the design. The whole aircraft was pressurised, including the cargo bay. The fuselage was strengthened by the ‘double layer’ required and contributed to the durability of the aircraft.

A turbine Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) was installed in the C-130. It was only the second such installation on any aircraft, the first being on the Douglas C-124.

“…you will destroy the Lockheed Company”

Senior Lockheed officials were sceptical, advising the vice-president of Lockheed not to sign the prototype proposal document. “If you sign that letter, you will destroy the Lockheed Company.” They thought that the Hercules would not sell enough to recover the development costs. The document was signed, and the company won the contract in July 1951.

The first flight of the prototype YC-130 took place in August 1954. The aircraft was more manoeuvrable than expected and met or exceeded all USAF requirements. The transport pilots were delighted. The C-130A, at a weight of 45 000 kg, was labelled as overpowered, could climb at 2 500 ft/min and comfortably fly with one engine out.

Lockheed-Martin describes it as “The C-130 is whatever is needed, it’s an ambulance, it’s a gunship, it drops paratroopers, it carries cargo, it’s a T.V. broadcast system, it’s launched drones, and caught satellites. You name it, the Hercules has done it at some point in its career.”

The military transport aircraft was now a mature design, and its versatility had an incredible impact on world affairs.