Des Barker

Ask any SAAF fighter pilot that has flown high performance jets what his favourite aircraft was and the answer will in all likelihood be the Mirage F1, whether the interceptor version, the Mirage F1CZ, or the ground attack version, the F1AZ.

There is no doubt that Dassault’s swept-wing Mirage F1 overcame most of the performance and handling shortcomings for which the early delta-wing designs were renowned.

BACKGROUND

Designed as a single seat, all-weather, air-superiority fighter as the successor of what had become Dassault’s trademark; the Mirage III series of delta wing interceptors, the Mirage F1 found its way into the heart of many a fighter pilot, particularly those of 3 Squadron, South African Air Force.

DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

Whereas the Mirage III was a first generation delta-winged design based on 1950’s aerodynamics and propulsion knowledge, the swept-winged Mirage F1C was a major step forward in supersonic interceptor design.

Most importantly, the swept wing design retained the supersonic interceptor capabilities originally designed into the delta-winged aircraft to counter the Cold War threats posed by the Soviet bombers and fighters from the Tupolev, Sukhoi and Mikoyan design bureaux while simultaneously improving the ‘dogfight’ capability. This multi-purpose capability had a further spin off in that the Mirage F1 design could also be used in the ground attack role, hence the development of the Mirage F1AZ.

Developed and financed at own risk by Dassault, the prototype Mirage F1 made its first flight on 23 December 1966 and was accepted by the French Air Force in May 1967. Besides the wing planform change, the most significant design changes were the larger capacity Snecma Atar 09K50 turbojet producing nearly 2,000 lbs more static thrust than the 13,700 lbs of the Mirage III’s Atar-09C and the introduction of more modern navigation, weapons and avionics systems.

In an effort to improve the handling qualities at high angles of attack, the swept wing was provided with leading edge slats and automatic combat flaps to subsidise turning performance which enabled the Mirage F1 to outclass most contemporary fighters in close combat. In order to comply with the French Air Force’s requirement for an all-weather interceptor, the first production Mirage F1C was equipped with Thompson-CSF Cyrano IV mono-pulse radar.

The Mirage F1C eventually entered service with the French Air Force in May 1973 but strangely, initially was armed only with two 30 mm internal cannon, since missile development was behind schedule. It was only in 1976 that the Matra R530 medium-range semi-active air-to-air missile was released to service and was followed a year later by the short-range infra-red Matra R550 Magic. At the time, this armament combination provided the F1C with a potent mixture of air defence ordnance to counter high speed enemy intruders. The later production Mirage F1C-200 with a fixed refuelling probe served as the main interceptor of the French Air Force until the Mirage 2000 entered service in 1983.

SAAF DELIVERY

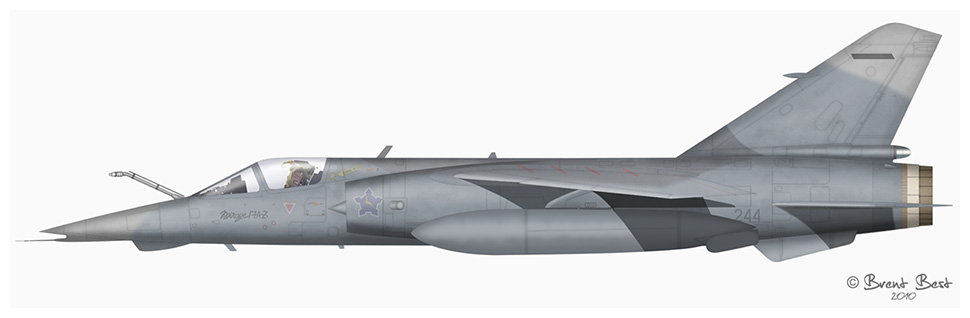

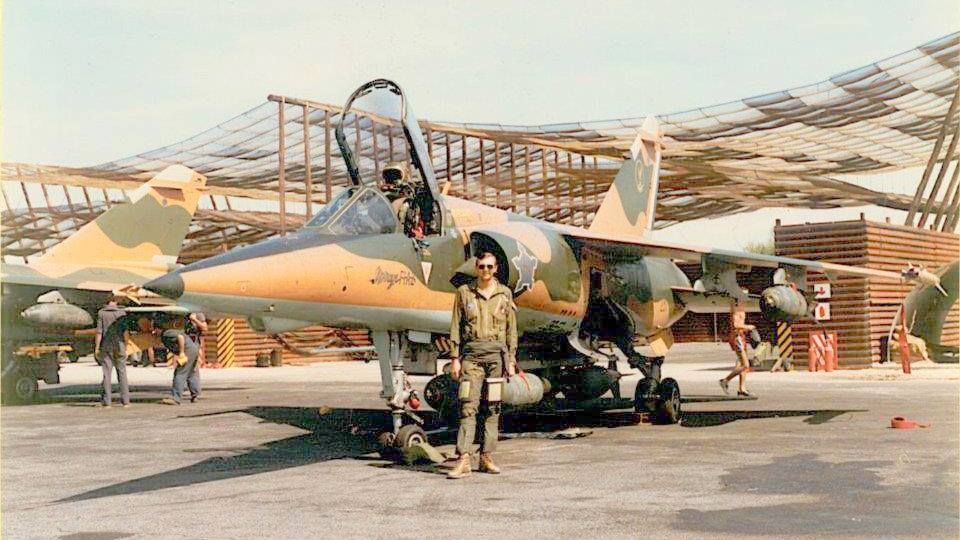

Realising the potential of the design, Dassault’s subsequent Mirage F1 production was customized for an additional two roles, ground attack and tactical reconnaissance. Despite the arms embargo imposed on South Africa by the United Nations during the 70’s, Dassault had no qualms about selling 48 Mirage F1s to South Africa to complement the already large number of Mirage IIIs in SAAF service. In fact, the SAAF became the launch customer for Dassault’s Mirage F1CZ while the Mirage F1AZ was developed by Dassault specifically for the SAAF as the ground attack variant. Considering the international political pressure of such an acquisition, the first two aircraft of the 48 ordered were delivered on 5 April 1975 under a blanket of security and the remainder (including 32 F1AZs) followed in July 1975.

AERODYNAMICS

Military fighter designs are traditionally influenced by the existing aerodynamic and propulsion capabilities versus the prevailing threat. In the USA, third generation fighter design was originally signalled by the introduction of the delta-winged F-102 and F-104 to counter the threats posed by Cold War interception requirements. The call was for efficient supersonic flight that would enable the interceptor to be scrambled, accelerate and climb to a supersonic interception of Soviet bombers, launch the air-to-air missiles and return to base. Dogfighting was not really considered an essential capability for an interceptor and in those days, technology did not really allow for efficient multi-purpose designs.

The aerodynamically stringent performance requirements demanded the low wave drag characteristics of the delta wing. However, the disadvantages at high angle of attack flight, and the low lift curve slope gradients, eventually forced designers to compromise by rather using swept wings to reduce the low airspeed, high induced drag characteristics of the delta while retaining the higher critical drag rise Mach Number of the swept wing.

Sadly, by the late 1970s, it became apparent to aerodynamicists that due to the induced drag penalties of delta wings and inadequate flight control technology, the utilisation of such wing planforms would only be sustainable in future by the use of fly-by-wire and negative stability margins. Delta wing fighter design therefore quietly faded into obscurity as designers chased after swept wing planforms to meet their interception requirements. The introduction of fly-by-wire systems by the 1980s enabled designers to select practically any wing planform and life was once again breathed into Dassault’s beloved delta wing configurations such as the Mirage 2000 variants.

Dassault, in keeping with a developing trend in Europe at the time, chose a swept wing mounted high on the fuselage which gave the Mirage F1 its rather aggressive look when viewed from the front. Wing sweep generates an unusually high roll response to sideslip and in an effort to provide rolling agility and neutralise the dihedral effect, the wings were mounted with anhedral.

TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCES

Considering that SAAF fighter pilots were flying Mirage III, Sabres and Impalas during the 1970s, the latest technological advances that were introduced by the Mirage F1CZ had a significant impact on SAAF operational capability.

A modern fire control radar, semi-active radar and latest generation IR missiles, flight refuelling, and an autopilot that was everything a fighter pilot ever wanted, were just some of the technologies that in the 1970s allowed the SAAF, technologically, to achieve parity with most first world air forces.

Referred to respectfully as ‘Sir Ponsonby’ by some of the F1 pilots due to its dynamic performance throughout the flight envelope, and in contrast with the older generation transport aircraft autopilots, that were affectionately known as ‘George’, this autopilot allowed automated flight in all missions except dogfights and low-level tactical flying. It was the quick and predictable response of the autopilot that flew the aircraft like a fighter, not a transport aircraft, that won it most of its accolades.

Then of course, and most importantly, with a significant increase in internal fuel load, the F1CZ could no longer be referred to in disparaging terms by transport and helicopter pilots. Calls that:

“The Mirage III is the only aircraft that can see its point of no return while on the runway threshold”.

In reference to the very limited fuel payload of the Mirage III, were common ‘chirps’. The fact that the Mirage III could reach its destination in a fraction of the time was always quite conveniently forgotten by the critics.

The addition of a flight refuelling capability increased endurance to more than five hours which was ideal for combat fighter sweeps and combat air patrols which in effect was a force multiplier in the context of the limited numerical assets of the SAAF.

Pilot workload remains one of the major challenges in ‘dogfighting’. In the case of the Mirage III, this was exacerbated by the high induced drag of the delta wing and the consequent high energy bleed rates. With a minimum drag airspeed of 280 to 300 KIAS, energy management was a serious challenge to the pilot which, coupled with significant adverse elevon yaw below minimum drag speed, required a concerted and coordinated effort to use rudder to counter the adverse yaw of the elevons. These factors all made air combat manoeuvres challenging, not only to co-ordinated flying, but also in terms of physical workload. These factors cost many a Mirage III pilot the tactical advantage if the aircraft was not flown optimally.

With hydraulically powered, full electro-mechanical controls, the F1CZ design engineers were able to produce harmony about all three axes utilising spoilers to counteract adverse aileron yaw with pitch and yaw dampers and automatic rudder trim to further reduce pilot workload to fly the aircraft accurately throughout the entire flight envelope, all the way out to Mach 2.2. Such delightfully balanced controls made it easy for the pilot to focus on weapons system operation and combat tactics instead of having to focus on aircraft handling. These relatively easy handling traits contributed to fighter pilots classifying the Mirage F1CZ as a ‘gentleman’s fighter’.

Speed and weapons capability define an interceptor’s capabilities and as such, the F1CZ was provided with a mix of MATRA 550 ‘Magic’ short-range Infra-red (IR) missiles fitted on wing-tip missile rails and the longer range radar guided MATRA R530 which could be carried either under wing or under fuselage. However, the R530 proved to be ‘technically challenged’ by the demanding conditions of Africa and due to the number of problems experienced, the MATRA R530 was withdrawn from service after the initial testing phase.

The Mirage F1CZ retained the twin internal DEFA 30mm canons similar to the type used in the Mirage III. Quite surprisingly though, the only two kills achieved by the Mirage F1CZ in combat during a time in which missiles were regarded as the weapon of choice, were by the DEFA cannon, not air-to-air missiles.

LOCAL DEVELOPMENT

The imposition of the UN Arms Embargo led to the establishment of a local armament industry within the RSA which had, as one of its objectives, to increase the capabilities and survival indices of the SAAFs fighter aircraft through improved air-to-air missile capabilities, active and passive electronic warfare capabilities and even propulsion systems.

It must be remembered that the F1 was essentially mid-1960s technology, at best early 1970s. By the time the F1CZ entered the Angolan conflict, the Mirage F1CZ technologies were already more than ten years old and modernisation to compete against Soviet technology employed by Cuban Forces in Angola, was essential to maintain the balance of power.

As the SAAFs primary air defence fighter at that time, the focus was obviously on the development of a locally designed air-to-air missile. The V1, similar in appearance to the AIM-9B, was designed in 1969 by the National Institute of Defence Research which saw the establishment of a new local missile company Kentron (later Denel). Even though the V3A entered service in 1978, work was started almost immediately on the V3B “Kukri”.

Such was the success of Kentron’s development programme that a new air-cooled IR seeker was developed which could be slaved to an indigenously developed, helmet-mounted sight; the forerunner to the helmet sight currently being used on Eurofighter Typhoon and Gripen. This system offered the pilot the capability to achieve off-boresight missile lock-on.

The B model introduced a new improved rocket motor, a more sensitive IR seeker, better target discrimination and improved counter measures resistance. The V3B, which entered Service in 1982 as the standard missile available on the Mirage F1CZ was, nonetheless, still effectively a tail aspect missile with a maximum range of between 2 – 4 kms.

However, greater range and an all aspect capability was urgently needed to counter the Russian missile technology employed by the Angolan Air Force’s MiG-23s and Kentron set about developing the next generation air-to-air missile for the Mirage F1CZ, the V3C (U-Darter). With increased maximum range, this was the first air-to-air missile fitted to the Mirage F1CZ with an all-aspect capability but, due to developmental time lag, it only entered service on the Mirage F1CZ in the early 90s, too late for operational use.

There is no doubt that the Mirage F1CZ was a capable interceptor and ‘dogfighter’ in the air defence configuration of 825 litre belly tank, two V3C IR missiles and two 30mm DEFA cannons. But, in an effort to keep abreast with technologies being introduced to Soviet aircraft in Angola in the 1980s, and to provide an increased combat thrust-to-weight ratio, the SAAF had no other option but to upgrade the engine and the air-to-air missiles. [This engine upgrade is coved in the separate box after this article.]

The missile on offer was the Russian AA-11 ‘Archer’, which even by today’s standards, remains in service with several air forces in the world and is considered a highly capable missile. It is no secret that Soviet missile technology was ahead of that in the West at that time. The missile was cleared for carriage on the Mirage F1AZ and F1CZ and would have provided a major improvement in IR missile capability for the SAAF, bringing it back at least on par with the MiG-23s that were encountered in the Angolan war. However, the cessation of the UN Arms Embargo enabled access to state-of-the-art technology that could be purchased ‘off-the’ shelf’ and as such, the requirement to develop the Mirage F1CZ further could not be justified.

During the Angolan conflict, the SAAF faced a potent air defence network comprised of anti-aircraft systems, hand-held, mobile and fixed base surface-to-air missiles (infra red and radar guided), extensive surveillance radar coverage, agile short range fire control radars and radar controlled anti-aircraft guns. There was nowhere left to hide for SAAF fighters and the only way of increasing the survivability indices of the SAAF’s fighters, was to introduce radar warning devices. The combination of radar warning systems and tactics enabled the SAAF to emerge as one of the most skilled forces at negating the threat of electronically controlled air defence systems.

First to be introduced on the Mirage F1CZ was the Radar Warning Receiver. Ongoing development of these systems eventually led to South Africa becoming a leader in this field under Grintek which even today continues to provide electronic warfare systems, not only for the SAAF, but also for several foreign countries.

But as the pilots flippantly pointed out, the early variants of these systems were rather a device that indicated how quickly you were about to die. The next step was the introduction of active and passive counter measures coupled to the Threat Warning Receivers to automatically neutralise the electronic threats. On the F1CZ this was a high priority and the first chaff and flare systems were installed inside the modified ventral fins.

COMBAT RESULTS

The only true test of character for any fighter aircraft is how it faired in actual combat. Considering that the users of the Mirage F1 were essentially in Africa and the Middle East ‘hotspots’, is it any wonder then that the F1 was involved quite extensively in air combat where it came up against both Western, as well as Soviet fighters.

The first combat deployment of the French Air Force Mirage F1s was in 1983 to Chad. Using F1C-200s for combat air patrol, one Jaguar was shot down while an F1C-200 was damaged in early January 1984.

Iraqi Mirage F1EQs were kept busy fighting the Iranians during the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s, with the F1EQs claiming destruction of at least 35 Iranian aircraft, mostly McDonnell F-4 Phantoms and Northrop F-5E Tiger IIs and also, amazingly, one Grumman F-14 Tomcat, shot down on 22 November 1982. Seven F1EQs were lost in combat, and several were flown back to France in Iraqi Ilyushin Il-76 transports for the repair of extensive battle damage.

The 1990 Gulf War was the culmination of the Mirage F1’s combat career, with the type being operated by both sides in the conflict. The Iraqi Mirage F1EQs saw a good deal of combat on the losing end of the battle. Three F1EQs were shot down by US Air Force (USAF) F-15 Eagles using AIM-7 Sparrow AAMs on 17 January 1991, with one more lost in an accident while mixing with a USAF F-111 Aardvark on the same day. In fact, the Mirage F1EQ was the first Iraqi aircraft to be lost in air combat in the war.

Two more F1EQs were shot down by USAF F-15s on 19 January, with another two lost to a single Saudi F-15 on 24 January. One final kill on an F1EQ was scored by a USAF F-15 on 27 January which left the final score of F-15s versus F1EQ as 8 – 0 to the F-15s. The contest was clearly unequal, but Iraqi handling of air combat in the conflict was apparently unbelievably timid and the F1EQs might have done a bit better for themselves with better pilots.

In the Mediterranean theatre, Mirage F1CGs have had occasional run-ins with Turkish fighters, with Greek F1CGs and Turkish F-4 Phantoms getting into bloodless engagements over the Aegean Sea. One F1CG was lost in an accident in 1992 while trying to intercept two Turkish F-16s. (Greg Goebel -In the Public Domain: Sep 05)

In SAAF context, two dogfights that were well publicised involved SAAF Mirage F1CZ #204 and F1CZ #203. Interestingly enough, the pilot in both instances was 3 Squadron’s Major Johan Rankin. On 6 November 1981, two F1CZs were scrambled from AFB Ondangwa after two MiG-21s had been detected on radar approaching South African ground forces deployed in Angola. They flew at low-level up the Cunene River staying below Angolan radar cover and then pitched to 25,000ft. Undetected by the MiG-21s, they jettisoned their drop tanks as they entered a hard left turn that brought them directly behind the unsuspecting MiGs flying 1,000 metres apart. Closing from the rear, Rankin fired a short 30mm cannon burst striking the wingman’s aircraft. The bandit’s attempted evasive action brought the MiG into the sights of Rankin who fired a further burst of 30mm cannon. The MiG exploded as the pilot ejected to safety and Rankin had to take evasive action to avoid flying into the debris.

In another dogfight on 5 October 1982, two Mirage F1CZs were escorting two 12 Squadron Canberras that were carrying out photographic reconnaissance overhead the Angolan town of Cahama. Mission controllers detected two unidentified ‘bandits’ approaching the Canberras and instructed the Canberras to egress southward to safety and directed the F1CZs towards the bandits which were identified as MiG-21s.

The two F1CZ pilots pitched to 30,000ft and found they were approaching the MiGs head-on at a closing velocity approaching twice the speed of sound. They jettisoned their drop tanks, selected afterburner and at the cross, started a hard right-hand turn in pursuit. The MiG-21s had fired their missiles just before the cross but without success. Closing in on the MiGs, Rankin fired a missile but the range was excessive and the missile went ballistic. He fired the second missile at the lead MiG from 1,500 metres and it exploded close to the MiG, damaging it. Rankin closed on the wingman and fired the 30mm cannon which struck the MiG, causing it to explode. Subsequent reports received indicated that lead MiG’s aircraft was unable to lower its undercarriage which required the pilot to conduct a belly landing, causing substantial damage. (SAAF FAPA Dogfights, Winston Brent, 9 Jan 2006)

Up to that stage, the balance of power had been relatively equal within Angola. With the introduction of the MiG-23ML “Flogger G” by the Angolan Air Force, however, the whole scenario in Angola changed. Designed for air defence tasks, they were equipped with frontal aspect air-to-air missiles, which brought a whole new twist to counter air missions. Without frontal aspect missiles, the Mirage F1CZ could no longer afford to engage in air combat; a bit like taking a knife to a gunfight; the probability of success is extremely limited and the employment philosophy was forced to change which in effect, severely restricted Mirage F1CZ operations during daylight hours.

Total avoidance of combat within an operational environment cannot be guaranteed. The only Mirage F1CZ lost in the Angolan conflict to a counter air mission was #206. On 27 September 1988, Captain Arthur Piercy flew his damaged aircraft back to AFB Rundu after it had been struck by an AA-8 (Aphid) air-to-air missile fired from an Angolan Mig-23 – exactly the scenario the SAAF were trying to avoid.

After a successful landing but without wheel brakes or drag chute due to missile fragmentation hits, landing the Mirage F1CZ on a very short runway was always going to be challenging. The result was that his aircraft overshot off the end of the runway, struck a ditch, the force of which caused his seat to eject him from the aircraft and since there was insufficient height for the parachute to open fully, Piercy impacted the ground in his seat, seriously injuring his lower back and spinal cord. Today, he is restricted to a wheelchair as a paraplegic. Fred Bridgeland’s book “War for Africa” details this combat mission comprehensively. Following this tragic accident, the SAAF, wisely chose not to challenge the Angolan MiG-23s in air-to-air combat. Piercy’s aircraft was also the last aircraft to be involved in air combat.

CONCLUSION

There is no doubt the acquisition of the Mirage F1CZ was a quantum leap in air defence capability for the SAAF. The introduction of the next generation of aerodynamics and navigation weapon’s systems provided a significant increase in dogfight capability for the SAAF in the 1970s. Although the Mirage F1CZ was prematurely retired from service in 1992, there is no doubt that in the minds of the pilots that flew her, she was one of the great fighters of the time, in fact, a gentleman’s fighter!